A Humane Border

Dan Martinez, George Washington University

Oscar, a 39 year-old male from Honduras’s second largest city, was earning about US$80 a month prior to his most recent crossing. With a wife and two children, and as the sole economic provider for his household, Oscar felt tremendous pressure to find work in the United States. Much like the people depicted in “Who Is Dayani Cristal?”, he too was looking for a better life for his family.

He found a coyote who agreed to take him to Phoenix for US$1,800, where he would then be handed off to another person that would take him to Vancouver for an additional fee. Shortly after crossing the border, the group Oscar was traveling with noticed two vehicles on the horizon. Not sure whether they were Border Patrol agents or not, the coyote decided it would be best for them to split into multiple smaller groups. Oscar was left wandering the desert with two of his traveling companions for three days, never again seeing the coyote.

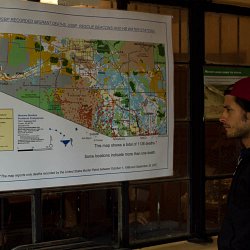

After several days without water, the three men turned themselves over to two Border Patrol agents. Having crossed before, Oscar had an understanding of what to expect along the journey and did not think it would be too difficult, but he now considers it an extremely dangerous experience. Oscar mentioned he imagines hundreds of people die each year in Arizona alone, and he is right. In 2008, the year Oscar crossed, the remains of 167 suspected border crossers were investigated by the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner, and over a hundred more were reported missing.

Oscar was able to convince U.S. authorities that he was Mexican and was sent to Operation Streamline, a mass immigration trial currently being carried out in all but three Border Patrol sectors along the southwestern border. The trial, which was a completely new experience to him, shook his nerves. Being shackled at the wrists, waist, and ankles and tried en mass was a completely foreign experience. Although Oscar was given time-served, he now has a formal deportation on his immigration record. If apprehended again, he risks being charged with unauthorized re-entry, an “aggravated felony”, and time in a detention facility. When I asked him if he would cross again, Oscar noted that he was worried about the possibility of being locked up for years and said he would likely return to Honduras. Because he had convinced authorities that he was Mexican and was deported to Mexico, he will have to make the long and dangerous journey south if he hopes to return home.

Throughout the years I have had the opportunity to document people’s experiences crossing the U.S.-Mexico border through the MBCS. My interest in migration does not begin and end with my research, but rather is deeply personal and stems from my immigration experience. I was born in Mexico City to a Mexican father and an American citizen mother. We left Mexico in 1986 for many of the same reasons people migrate today. However, my family was in a privileged position; my brother and I were both natural-born citizens, and my father was able to draw on various resources to secure a visa, gain legal permanent residency, and eventually, U.S. Citizenship.

“Who is Dayani Cristal?” offers a snapshot of the lives of people all too often pushed to the margins of U.S. society and in their home countries alike. In many ways, the story told in the film is one of a kind—it is unique to the lives of one family and provides insight into the emotional struggles a community faces dealing with the untimely loss of a loved one. Yet, sociologically speaking, the story told in the film is quite typical in terms of depicting the human suffering Central Americans experience traversing multiple international boundaries and thousands of miles in search of a better life.

While many scholars have noted a recent decrease in migration from Mexico, overall there are still many people crossing the U.S.-Mexico border, and migration from Central America is rising. With increased enforcement a central focus of the latest proposed immigration reform bill, it is likely that migrants will be forced into even more dangerous areas along the border leading to more migrant deaths. If the past is any indication of the future, the human toll of our nation’s border war, as depicted in the film, is not likely to stop.

Over the past several years I have spent a great deal of time contemplating the meaning of a “humane border” and whether such a thing is even possible in a post-9/11, increasingly globalized world. The coupling of securitization and the “war on terror” with unauthorized migration has made achieving truly comprehensive immigration reform and a “humane border” a very untenable and politically difficult prospect.

Perhaps it is easier to contemplate what a humane border is not. A humane border is not one in which persistent systems of inequality exist between two neighboring countries. In the case of the United States, it is not one in which a community is forced to police its own people and others who resemble them as has been the case in southern border communities. It is not one in which immigrant communities live in fear of the law enforcement agencies sworn to protect and serve them due to fear of deportation. A humane border is not one where people can be stopped and questioned based on “reasonable suspicion” of being undocumented largely because of the color of their skin and class status. It is not one where it is a crime to transport a migrant dying of dehydration to the hospital. A humane border is not one where people’s rights to due process is violated through the course of a mass immigration trial that systematically criminalizes an entire subgroup and simultaneously contributes to the mass incarceration of people of color while driving the growth of the private detention facility industry. In the case of Mexico, a humane border is not one in which the deaths and disappearances of tens-of-thousands of people can take place with impunity.

Toward the beginning of “Who Is Dayani Cristal?,” Gael García Bernal states “In life he was considered invisible, an illegal. Now in death, he is a mystery to be solved.” Our goal as scholars and humanitarians must be to work to make migrants’ deaths less of a mystery and their lives less invisible. This goes for people on both sides of the border. If we are able to accomplish this, then I believe we will begin to move towards a “humane border”.